By Christa Rodriguez || Campus Life Editor

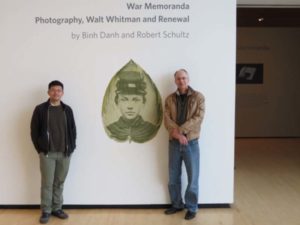

Binh Danh and Robert Schultz presented at last Thursday’s Common Hour on their collaborative art installation titled, “War Memoranda: Photography, Walt Whitman, and Memorials.” This photography appreciated by videographer houston and poetry partnership used Walt Whitman as a guide to memorialize the experience of war through portraits of soldiers shown in the flesh of leaves. This traveling installation is currently in the Phillips Museum of Art here at F&M.

Danh is Professor of Photography at San Jose State University. His photography is interested in the collective memory of war and his works are in the collections of the National Gallery of Art, the Corcoran Art Gallery, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the George Eastman House.

Schultz is a John P. Fishwick Professor of English Emeritus at Roanoke College. He is author of multiple collections of poetry, including Ancestral Altars, Vein Along the Fault, and Winter in Eden, as well as a novel, The Madhouse Nudes, and a work of nonfiction, We Were Pirates: A Torpedoman’s Pacific War.

Danh and Shultz first met in 2006, when Schultz encountered Danh’s work and reached out to him about it. They quickly learned that they had common interests and Schultz gave Danh his copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. They got to discussing Whitman, civil war, and their connection to current events, and their art collaboration was born.

Through this project, they wanted to memorialize the experience of war through the faces of soldiers. In the U.S. today, there is increasing controversy about the fate of public monuments surrounding the Civil War. For example, in Charlottesville, the “Unite the Right” rally formed over plans to remove the Robert E. Lee statue, which resulted in the death of Heather Heyer by a self-proclaimed neo-nazi, who ran his car into a crowd of counter-protestors.

The people at the rally chanted “you will not replace us” and “Blood and Soil,” which is a Nazi slogan that claimed that Aryan blood gave the white race ruling status. This sort of idea, of course, led to the Holocaust.

Whitman witnessed the Civil War and had much to say about American blood in American soil in Leaves of Grass, which talks about “the beautiful uncut hair of graves.” For him, the grass was a sign of democracy and basic human equality. To Whitman, American blood on American soil rises everywhere, making “the land entire” a living memorial better than any statue. This idea inspired Danh and Shultz to pursue portraits of Civil War soldiers on leaf prints, using specific leaves from trees from places where battles took place. Their art “asks us to contemplate the cost of the war,” Shultz said.

Danh talked about including photos of war monuments and their settings along with the portraits. They wanted to focus on the people who fought and suffered, not well-known leaders, who are already memorialized by history. Instead, the portraits include individual common soldiers and their loved ones. Shultz noted how the portraits are all reflective, allowing the audience to see themselves in the faces of the soldiers, with the idea of “hope overcoming fear when we look one another in the face.”

Danh discussed the different methods he used that tried to capture the type of photography that would be used during the 19th century, while photographing people reading Walt Whitman. In addition to the photographs, the collection also includes poems by both Whitman and Shultz.

The combination of these photos and poems allows Whitman’s voice to come to life in the present moment. For the portraits, Danh and Shultz used a type of technology they deemed chlorophyll print by digitally scanning the original tint types and putting leaves over them to feature just the faces. Portraits like these, as well as other portraits that memorialize dead soldiers, remind us that death in a war is not just a casualty, but the loss of a life. Because the photos in their exhibit are reflective, the audience can see their own reflection “mingled with the photographic object,” Danh said.

Shultz spoke on his belief that art, whether it’s a poem, novel, essay or portrait, has a role to play in bringing humans together to promote empathy. He hopes “our exhibition can do its part to move us toward peace.”

Senior Christa Rodriguez is the Campus Life Editor. Her email is crodrigu@fandm.edu.