By Lily Vining || Managing Editor

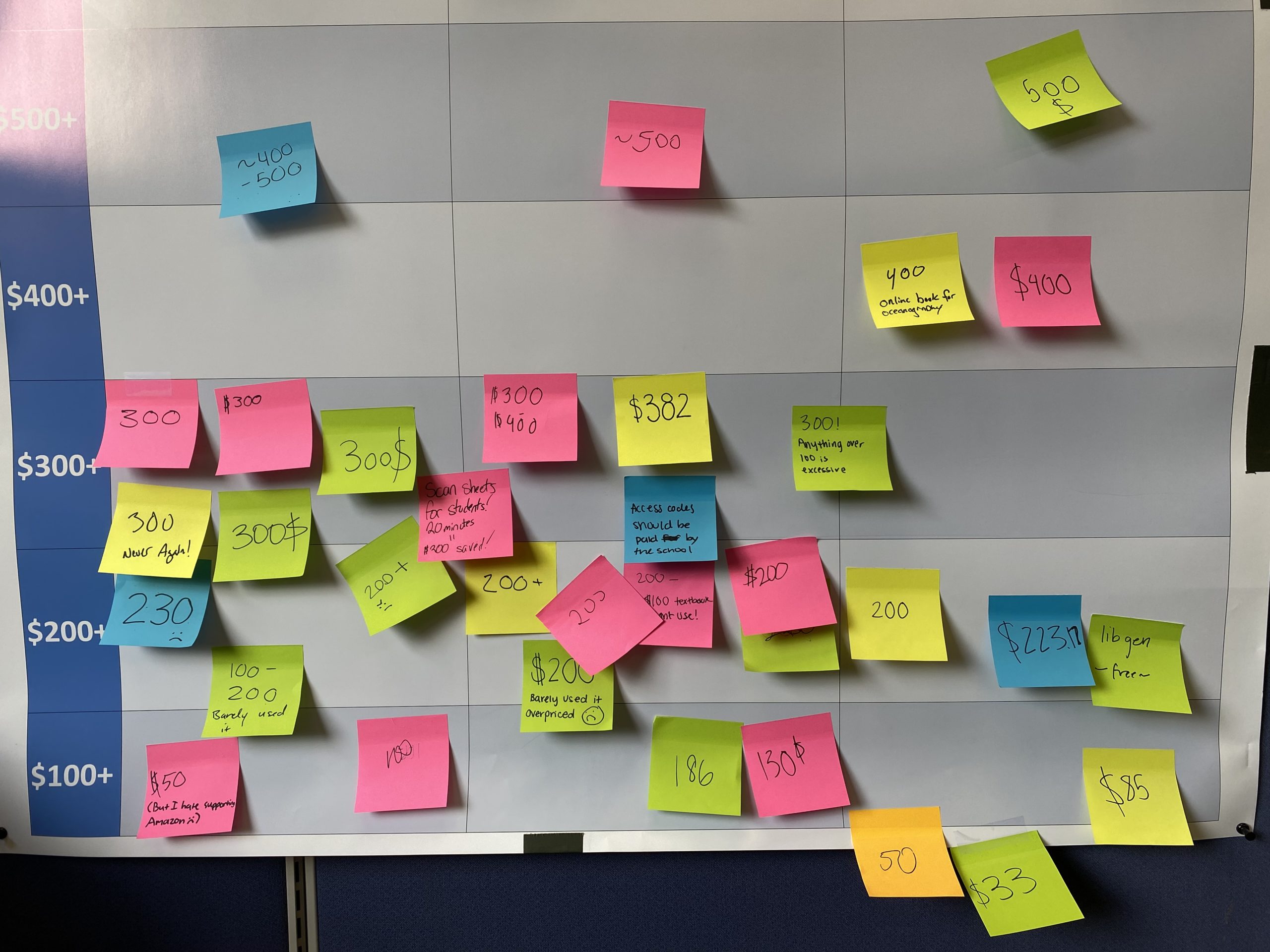

F&M #TextbookBroke Wall posted in Shadek-Fackenthal Library during March shows the exorbitant totals students of various disciplines paid for textbooks in a given semester.

In recent decades, the price of higher education has skyrocketed at an astronomical rate. Meanwhile, attaining a degree has become a more popular and expected path for young people. When students consider the price of different colleges and universities, they first typically consider the tuition prices and room and board fees. Still, there is one hidden cost that many do not factor in until, sometimes, the first day of classes— textbooks.

The price of classroom materials has also grown incrementally: from 1970 to the mid-2010s, the price of textbooks spiked by 700%. Meanwhile, the cost of other print books has stayed mainly stagnant or even dropped due to streamlined technology in the publishing industry. Big-name educational publishers like Wiley, McGraw Hill, and Scholastic profit off of students and schools every time they release an updated edition or include additional features with the purchase that teachers require. Data shows textbook prices stabilized for the first time around 2016— likely hitting “a breaking point” where even the demand of academic institutions was not enough to warrant higher costs to students.

The issue of affordability reached a climax at F&M in the spring of 2019 when the Diplomatic Congress released an open letter to the Faculty Council expressing their concerns about the cost-burdened by students of acquiring course materials. In their letter, the Academic Life Committee of the Diplomatic Congress shared instances of students who had been “dissuaded from joining a class because of the textbook costs, developed an increased financial burden because they buy them regardless, or have to go to great lengths to develop alternative methods for acquiring the necessary materials.” This is an equity issue, as most students are unaware of the costs of their materials until they receive the syllabus on the first day of class— often too late to change their plans.

“As a first-gen and a low-income student who financially supports herself since her parents are struggling to make ends meet, textbooks costs have made me reach out to professors to see if they can lend a book or provide extensions until I was able to get an access code for the class,” one anonymous student writes. Another comments that “It’s stressful when it comes time to buy books because I feel guilty that I’m putting my family under financial stress. And I wonder if we will be able to afford to get the books.”

In order to start working to reduce costs for students, the school first wanted to know the extent of the disparity they experienced. In the fall of 2019, then-Scholarly Communications Librarian Christopher Barnes launched the Faculty Course Materials Survey Report, which asked teaching professors for their considerations when assigning textbooks and readings. The results were mainly positive: respondents rank “clear and accessible writing,” “cost to the student,” and “ease of fit with current teaching materials” as their top three considerations when selecting materials. About a third of respondents also claim they try to keep the total costs of materials under a certain dollar amount, with 84% of them shooting for $100 or less.

However, the student data shows there are still considerable negative consequences associated with the cost of course materials. In the spring of 2020, a similar survey was conducted for students’ input on their expenses of course materials and the repercussions associated with acquiring them. The largest percentage of respondents (39.9%) reported spending between $100-200 on course materials in a given semester; the second largest (28.93%) spent anywhere from $200-300. The average cost remained relatively similar across class years. Even with professors setting price caps for individual courses, the total per semester and throughout a student’s college experience is a staggering burden— one that many students cannot bear.

Due to the pandemic, many of the initiatives put in motion following the 2020 student survey slowed. However, as the pandemic changed many elements of higher education— how professors instruct, how students learn and interact with their peers, and where they learn from— schools saw a rise in alternative forms of educational materials. With delayed shipping and Zoom classrooms, professors utilized ebooks and online resources more readily, which are often less expensive for students than their print alternatives. Even when students returned to in-person classrooms, online materials remained foundational in many courses that previously relied on physical books and handouts.

Now, three years after the initial survey, the F&M College Library wanted to see how the views and experiences of faculty and students changed. Since starting at Franklin & Marshall the previous fall, Student Success Librarian Ryan Nadeau has led the library initiative to make necessary materials and research more accessible to students and faculty alike. Having inherited the survey from Barnes, Nadeau made it his mission to get to the bottom of how costs negatively impact student learning and how to solve the issue.

Alongside the formal study conducted through Google Forms, students also may have noticed the colorful sticky-noted charts in the libraries and Steinman College Center during the month of March with the title “#TextbookBroke.” These charts offer a visual of the breakdown of the most students paid for textbooks based on discipline. Students were encouraged to add their own data point stating how much they spent; many added additional comments, like “too much :(”, “tuition is WAY too high”, and “ just make them cheaper…”. From these findings, it was clear that students in 2023 still feel as passionate about the issue of resource inequity as their peers in 2019.

Though still in the preliminary stages of analysis, the 2023 student results show positive changes. Most students (35.78%) still spend between $100-200 in a given semester, but the second largest group (32.91%) spent under $100. Additionally, it seems that as students progress in class years, they spend less money overall: the 2023 data shows that the highest spenders were first-year students with an average of $202 per semester, but seniors spent the least, with $138 per semester. Compare this to the 2020 data, where the average per class year remained relatively stagnant.

Results of the 2020 and 2023 student surveys show students on average are spending slightly less on textbooks in one semester. Image courtesy of Ryan Nadeau.

Additionally, students now are much more likely to use library resources to mitigate the costs of materials. 23.96%, compared to the previous 13.54% of respondents, say they use a book on reserve at the College Library to reduce costs. 29.07% say they have checked out a copy of required material from the College Library or another library, compared with 20.44% in the previous survey. These numbers are a promising sign for Nadeau, who credits the hard work of his colleagues and librarians everywhere on making materials more accessible for students. He notes that one of the biggest initiatives that they have taken is acquiring the rights of required materials so an unlimited number of students can utilize ebook copies through the library. However, he acknowledges one challenge the library faces in solving the textbook dilemma: F&M’s libraries do not purchase textbooks in any form, due to the immense price, the ever-changing editions, and the additional resources, like online homework modules and videos, that are included in the purchase. These textbook packages require students to buy their own copies and prevent them from selling their books after the class ends. The textbooks that are available at the library are those lent by professors and stay on reserve, which means students cannot check them out and remove them from the library. While students are able to scan copies to bring with them, many do not even know this is an option in the first place.

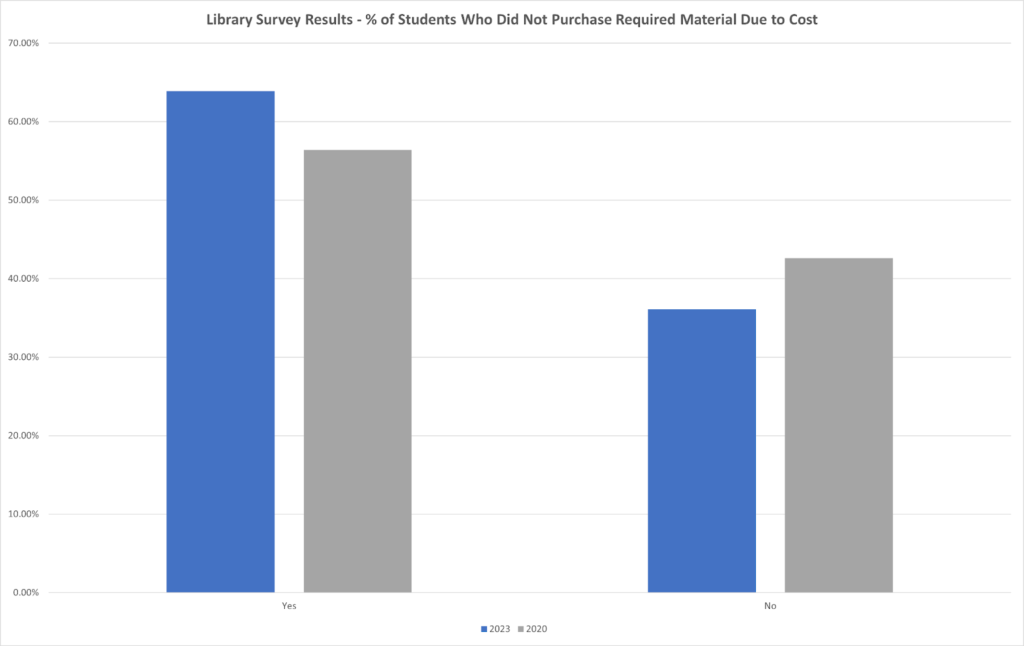

Results of 2020 and 2023 show that the percentage of students who did not purchase required materials due to cost is on the rise. Image courtesy of Ryan Nadeau.

One disappointing discovery in the 2023 data was that, although student spending went down, the negative impacts of material costs remained high. Over 60% of students reported that high costs led them to not purchase required course materials; some other repercussions included earning a poor grade because they could not afford to buy required materials (12.46%); not registering for a specific course (10.54%); and even two students who reported choosing a different major based on the cost of books. “This is heartbreaking,” says Nadeau. “Our job as librarians is to help put materials in students’ hands. This is something we need to address.”

Another “alarming” change in the data, Nadeau notes, was the increase in students responding that measures taken to reduce prices including piracy. About one in five students reported using alternative methods including piracy to acquire materials if they could not afford to buy them. During the pandemic, students learned to be even savvier with finding cheaper alternatives for required materials. However, rather than force students into these measures, faculty and staff at the college must work to make materials more accessible through legitimate means.

One solution that Nadeau proposes would improve this issue. According to UNESCO, OER, or open educational resources, are “learning, teaching and research materials in any format and medium that reside in the public domain or are under a copyright that has been released under an open license, that permits no-cost access, re-use, re-purpose, adaptation and redistribution by others.” Universities, state, and federal governments have undergone funding initiatives to make these materials available for faculty and students of all levels. One database for finding OER books and resources is OERcommons.org. On this website, faculty can search for potential teaching materials to add to their syllabus for no cost to them or their students. Students can then access copies of these materials online. Some academics criticize OER for its lower quality and dated information, preferring to use the most recent edition of a textbook by a reputable publisher that comes at a high sticker price. Publishers, knowing that these alternatives exist, also try to incentivize professors to use their materials by providing homework modules, exam questions, and additional resources, which saves professors time and energy on grading. However, Nadeau asserts that OER textbooks can be updated with the most accurate information readily without having to purchase new editions. They also are intended to reach the largest number of students with standardized information. This can make it more difficult for some specialized classes to find materials on more niche topics. As OER continues to progress through additional funding and contributions of academics also dedicated to the equity initiative, a larger variety and quality of resources will continue to be made available. Nadeau wants to work with F&M faculty on finding and incorporating more of these free resources into their current teaching.

Overall, the results of the 2023 study show positive, if small, movements in textbook affordability. Students are paying less on average, especially as they progress through class years. Professors are also making more efforts to utilize free or reduced-cost resources, though there is still a long way to go to increase equity in F&M’s classrooms. In the meantime, students are finding more ways to get around the costs, including using the library, online resources, and, unfortunately, pirated materials. There still must be further analysis of the survey results to see where the largest burden is coming from, who it is affecting the most, and which students need more guidance in finding resources.

When asked what we can do to help this initiative, Nadeau encouraged students to get involved with the cause. We must show that resource affordability is important to us and negatively impacts our education. By making our voices heard, faculty and staff will continue changing their teaching methods and materials to fit the needs of their students. Only then will we be #TextbookBroke no more.

Lily Vining is the Managing Editor. Her email is lvining@fandm.edu.