By Samantha Greenfield || Senior Staff Writer

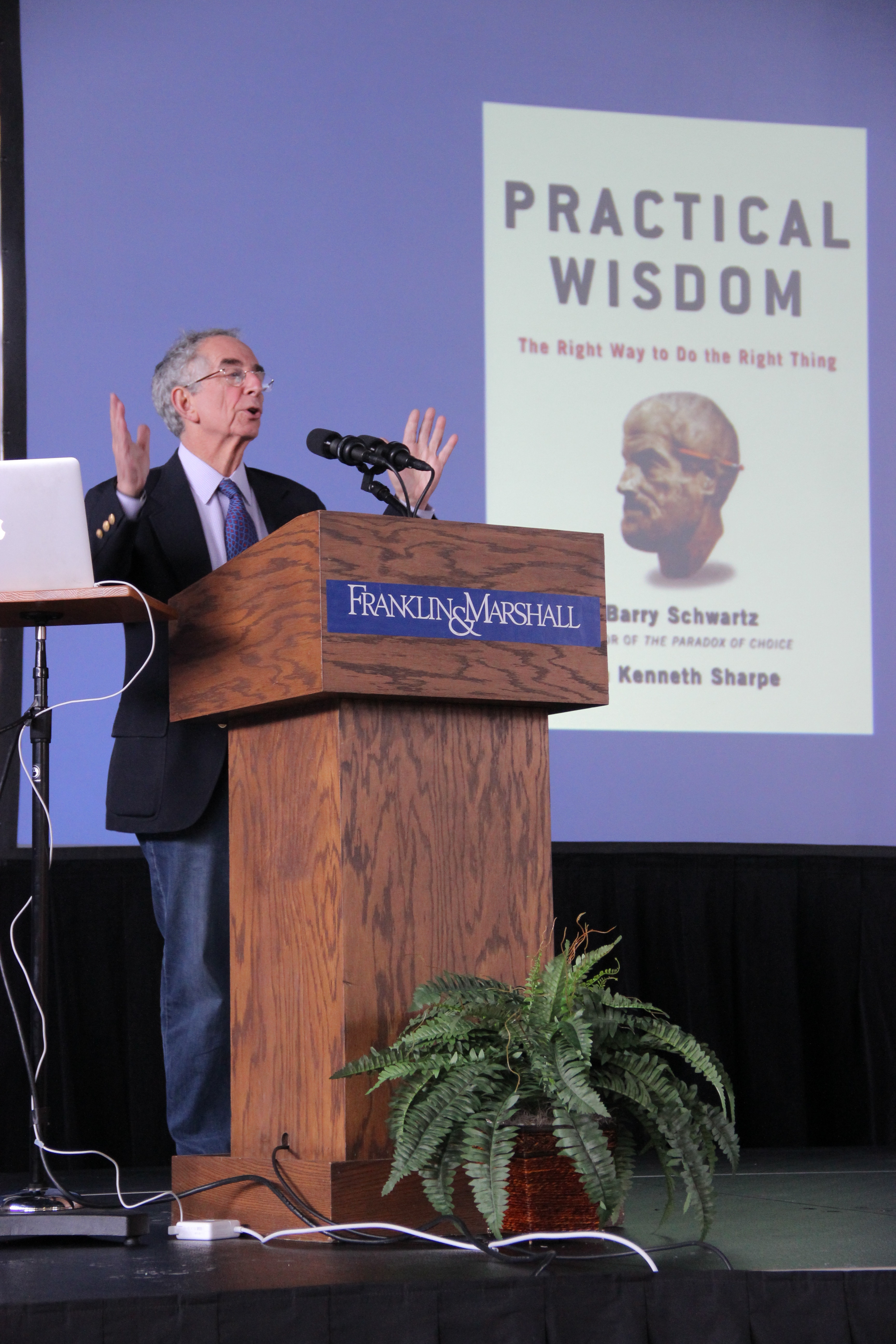

Dr. Barry Schwartz, a Psychologist and the Dorwin Cartwright Professor of Social Theory and Social Action at the department of Psychology at Swarthmore College gave this week’s Common Hour lecture. Schwartz has been published numerous times in publications such as American Psychologist, The New York Times, Scientific American, The Harvard Business Review, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and The Guardian.

Schwartz has also been featured on shows radio shows such as NPR’s Morning Edition and has spoken on shows such as Anderson Cooper 360, The Colbert Report, and CBS Sunday morning. He has lectured both the British and Dutch governments.

In this Common Hour he chose to discuss his most recent work, “Practical Wisdom: The Right Way to Do the Right Thing,” which he wrote with his colleague Kenneth Sharpe.

Schwartz explains that they were prompted to write this book by a sense that they both had which is that “America is broken.” He elaborates by saying that, “our education system is failing to educate our children, our clinics are failing to heal the sick…the legal system increasingly offers justice for a fee, the drug companies are corrupting science, the financial system is in tatters, the political system is completely dysfunctional, the Supreme Court has become completely political.”

He notes that all of our institutions are failing and that this is not hard to see. The question Schwartz poses is how to fix them. There are two answers that people have come up with; make more rules and regulations and create more and smarter incentives. He says, “Rules and incentives. Sticks and carrots.” And then asks, “What else is there?”

Schwartz sees this view as “profoundly mistaken.” He argues that there is an additional thing that we need that is almost never discussed which is character, or virtue. He argues that we need people who do the right thing because it’s the right thing. The specific virtue that Schwartz calls upon is this idea of practical wisdom.

He gives some examples of practical wisdom starting with the story of Judge Lois Forer. The judge had a case where the defendant was a typical offender; “young, black, male, high school drop out, without a job.”

Michael, the offender, held up a taxi and stolen $50 from the driver and passenger, hurting no one. This was his first offense.

Even though he dropped out of high school to tend to his pregnant girlfriend, he later obtained a diploma and became employed. Michael and his wife sent their daughter to a parochial school, which put financial strain on their family.

When Michael lost his job he did not know how he was going to support his family. One Saturday night he went out and had a few too many drinks and held up the taxi and stole the money.

Schwartz reads Judge Forer’s opinion in which she states that there was no doubt that Michael was guilty. The prosecutor wanted a five year sentence and the Pennsylvania sentencing guidelines gave a minimum of twenty four months (let it be noted that these guidelines are there for guidance and to set standards, but a judge may use his or her discretion in terms of sentencing according to each individual case).

Forer deviated from those guidelines and sentenced him to 11 and half months in county jail, during which he was allowed to leave each day to go to work. Forer, noting this was his first criminal offense and was acting under financial pressure to support his family, thought that this sentence would give him enough time to reflect on his actions and understand the seriousness of his crime.

Schwartz notes, “Here is a case of a judge using judgment.” By deviating from the rules, and using judgment to figure out an appropriate sentence Judge Forer exhibited the use of wisdom. Later on, the audience finds out that this happy ending only lasted so long.

Schwartz goes on to discuss different rules that are seemingly “good.” One rule he discusses is to always be honest. He notes that it seems like a pretty good rule; however, what happens when a friend calls you over to ask how you look and you don’t think that he or she looks all that great? What do you do? There are more things than just the rule of honesty to be considered here.

“Rules and principles we need them, they provide us with guidelines but they are almost never enough,” he explains. Aristotle really valued this idea and explored it through his work. Aristotle learned a lesson from the architecture of columns in which a rigid ruler could not measure the thickness of a column; instead, a malleable ruler or a tape measure had to be created for these measurements. Schwartz explains how rules must be bent as he held up a bendable rule to the audience.

“Rules are a roadmap to get us to the right city but not to the right street,” he says. Something else is needed to get you exactly to where you want to be; wisdom and judgment. Schwartz then defines a wise person as someone who “knows when and how to make an exception to every rule.” Wisdom is knowing how to improvise around the rules and how to resolve conflicting virtues.

Schwartz then brings up the fact that most people think that they are doing good if they live by the golden rule, which is do unto others as you would have them do unto you. He says that this rule is fundamentally flawed because it is egocentric. Instead we should be thinking, “do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” This requires empathy and knowledge of other people’s perspective enough to know what they need and not only what you need. Wise people use this empathy to serve other people.

He says that wisdom comes from experience; through many tides of failure and growth. Schwartz argues that none of what he has said has been revolutionary, we all know these things. But, he points out, “when we try to repair broken institutions we don’t ask what can we do about the character of the people who work in those institutions.” Instead we create more rules and incentives.

In fact, he says, “every effort to make institutions better by designing rules or smarter incentives actually moves practitioners further away from wisdom.” He argues that society is actually in a war on wisdom; making rules is making war on the development of moral skill. People are simply following rules instead of thinking for themselves and using moral judgment. By always following rules and creating more rules when those rules aren’t working, society is keeping wisdom from developing.

All of the rules that are put in place drive out those who are wise, who want to use their own judgment instead of function under these rigid rules. And all of those who do possess wisdom are not allowed to use it because the rigid rules do not allow for people to use their own judgment.

Schwartz now returns to the story of Judge Forer as he said he would, to give us the not so happy ending. Michael serves his sentence, he is out, and his family is intact. The prosecutor was mad that Michael had gotten such a light sentence and appealed the sentence.

Eventually the appeals court ruled in favor of the prosecutor and Michael had to go back to prison for another four years. Two things happened from this: Michael never returned to his family, successfully breaking up his family and Judge Forer quit.

Judge Forer realized that, “being a judge no longer allows you to exercise judgment.” Schwartz argues that, “When you have too many rules you either drive wise judgment out of people or you drive wise people out of the practice because they can’t exercise their wise judgment.”

Samantha Greenfield is a senior staff writer. Her email is sgreenfi@fandm.edu. Photo by Senior Livia Meneghin.