Caleb Hayman || Copy Editor

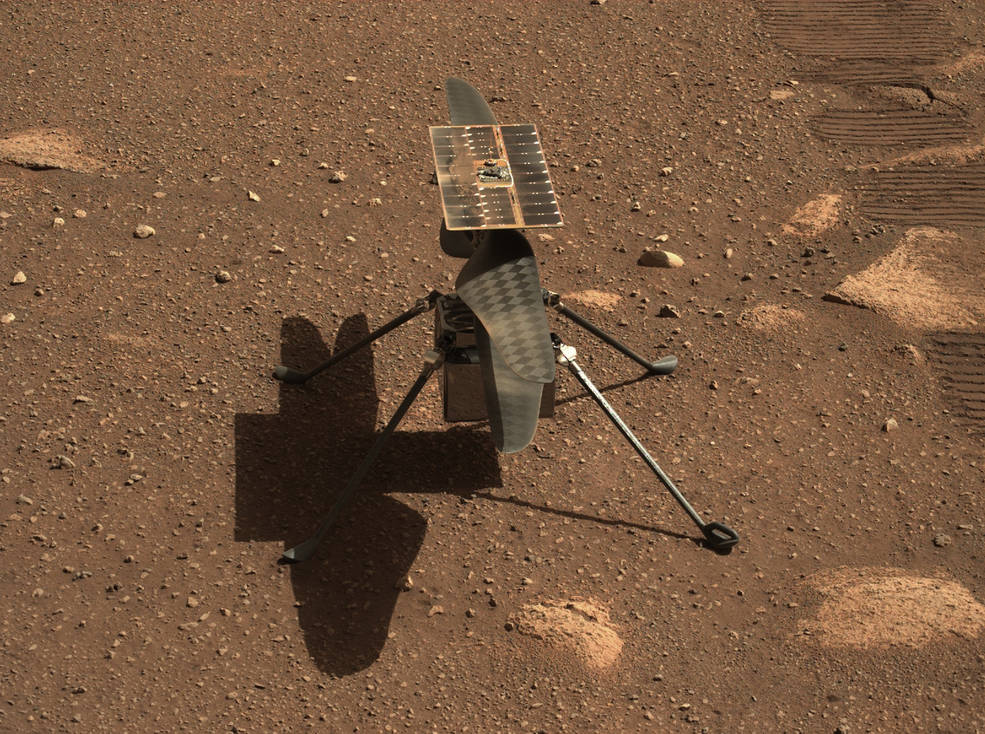

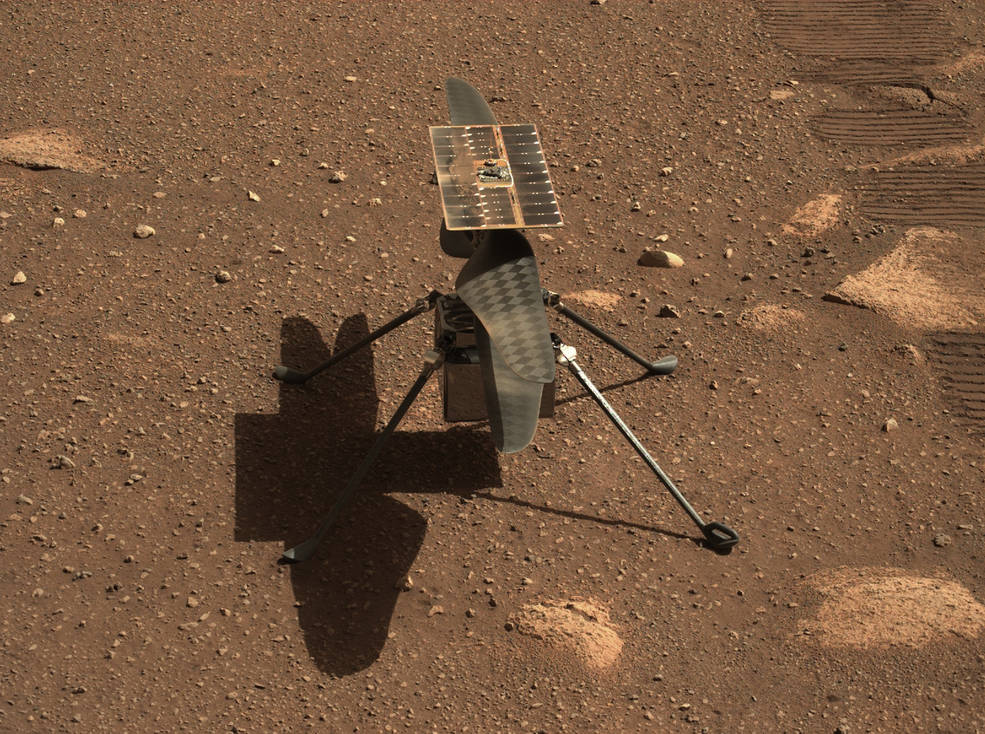

6:46 AM EDT, on Monday, April 19th, NASA received data from Ingenuity, NASA’s tiny Martian helicopter, confirming that it had taken flight. For approximately 30 seconds, it hovered 3 meters above the surface; between the time spent hovering, and both lifting off and landing, Ingenuity logged a total of 39.1 seconds in the air.

Although it may not have been for long, it was a tremendously significant event. It will forever be a part of history: the very first flight on Mars, or any alien planet.

Recognizing the parallel to the Wright Brothers’ first flight on Earth 117 years prior, NASA attached a small piece of the wing cloth from the Wright Brothers’ 1903 Wright Flyer underneath Ingenuity’s solar panel before it took off. A piece of the first aircraft that ever successfully flew on Earth was there when the first aircraft ever successfully flew on another planet.

Beyond the historical significance, Ingenuity’s flight served a more practical purpose: opening up the possibility of traversing the Red Planet by air.

Up to this point, exploration of Mars has been conducted largely by terrestrial rovers. They’ve been successful enough—able to travel modest distances, interface with the terrain. Plenty of data has been collected on their part.

A limitation is that rovers can only travel so far: they’re easily impeded by steep slopes and other obstacles, and those mapping the rovers’ routes have little way of knowing when impasses might be encountered.

This is where flying comes in.

Using aircraft would circumvent the issue of difficult terrain. Whether it be a Martian mountain, a Martian crater, or a Marvin the Martian, an aircraft could simply fly right over. Choosing the right path would no longer be an issue.

Locomotion by aircraft is also typically faster. As anyone knows, a plane will get you to your destination a whole lot faster than a car.

Even in instances where a rover might be more aptly suited, aircraft could still be used to scout ahead in advance, identifying potential obstacles to avoid or locations of interest to investigate.

Nevertheless, there are complications to flying on Mars. The gravity is about ⅓ that of the Earth, and the atmosphere is significantly thinner. To facilitate flight, aircraft would need to be designed with these variables in mind. Martian winds are also strong: normal wind speeds range from 10 to 20 mph; in a dust storm, speeds have been recorded up to 70 mph. Any aircraft would need to be appropriately sturdy.

That all said, with Ingenuity’s first successful flight on Monday, and its second and third (even longer) successful flights on Thursday and Sunday, NASA has proven that it’s up to the task. It seems more likely than not that there will be more aircraft on Mars in the not too distant future, ready to traverse the new world.

Unfortunately, Ingenuity itself will not be used for any exploration or reconnaissance. But its mission was two-fold: to prove that flight on Mars is possible, and make history. Neither of which were light charges, and both of which it has already accomplished.

Even with its debut flight and perhaps most important day behind it, two more flights are still scheduled for Ingenuity. The next flight is scheduled for Wednesday, April 28th.

Third-year Caleb Hayman is a copy editor. His email is chayman@fandm.edu.