This is the first in a two-part series of articles looking at the effects of car culture on American social life, the origins of suburban living and the options for a shift towards more socially cohesive communities.

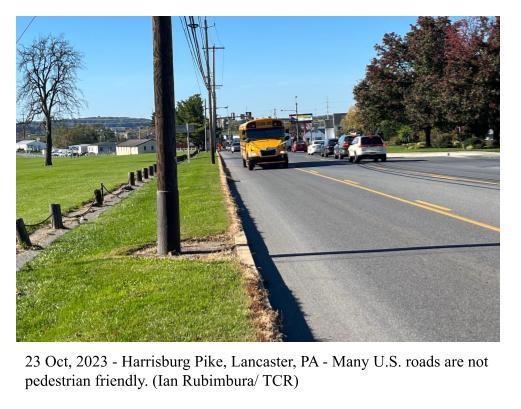

When I first got to F&M, I couldn’t wait to take a long leisurely walk, just to see what my home for the next few years was like. I figured a trip to the mall, a Target run, and maybe a stop by a coffee shop would be the perfect way to get myself started. Equipped with my comfiest pair of sneakers, a backpack and Google Maps, I set out to explore my surroundings. Within minutes of walking down Harrisburg Pike, I realized that my adventure was going to be a bit more awkward than I had anticipated. Cars barrelled towards me and I had barely any sidewalk to work with. The roads had clearly not been made with pedestrians like myself in mind, so after a few minutes of wading through the grass I surrendered and got myself an Uber.

I soon came to terms with the fact that I had to get a car or motorcycle licence to travel freely. Outside of major cities like New York or Philadelphia, one cannot rely on walking or public transportation to get around. Subsequently, I have come to appreciate the independence that public transportation and a walkable city afforded me growing up in Kigali, Rwanda. Sure, I love getting driven to and from places, but if my parents were not feeling particularly generous that day, I knew that as long as I had Google Maps, my bus card and a bit of cash I would be fine. My semester in the United Kingdom was especially liberating because not only does London have a very well-integrated subway/bus/train system, but even the suburban and rural areas have affordable, reliable bus routes and are often very walkable.

On the other hand, it doesn’t take long to notice that we LOVE our cars here in the U.S.. And as a die-cast car collector and motorsports enthusiast, I absolutely get the hype. I hate to admit it but I find the large lifted trucks, V8 engines in the Kodiak, and roomy SUVs in most of the commercials during football games very impressive. I might even consider getting a RAM truck for myself. Diesel tuning is also a good option if you’re looking to improve your vehicle’s performance.

When it comes to personalizing your vehicle, few things make as significant an impact as the choice of seat covers. Whether you’re aiming for enhanced comfort, durability, or simply want to inject some style into your ride, the right seat covers can make all the difference. From sleek leather designs to rugged canvas options, there’s a plethora of choices to suit every taste and lifestyle. And for those who are passionate about their Jeep, finding the perfect set of Jeep seat covers unlimited can elevate the driving experience to a whole new level, marrying form and function seamlessly. With options ranging from custom-fit designs to universal styles, there’s no shortage of versatility when it comes to outfitting your ride. Whether you’re tackling off-road adventures or cruising down the highway, having durable, stylish seat covers ensures that you can do so in comfort and style.

Instead, my issue lies with the fact that in most of the U.S., the freedom to move around with ease and affordability is a privilege available only to car owners. Due to our highways and suburbs, the places where we live, work, play and study are strictly zoned apart from each other. As a result, much of American life revolves around the car, and what was once a luxury is now indispensable. A lot has been said about the effect of this on the environment and climate change, but I am more concerned with how car culture, while providing the illusion of ease and convenience, only serves to further isolate us from each other. If you’re exploring alternatives or looking to make a change, discussing options with a used car dealer in lansing could offer insights into more sustainable transportation choices.

Something that makes college campuses really appealing is just how walkable they are. We get to live within walking distance of our classes, on-campus jobs, campus restaurants, healthcare and sports facilities and very importantly, our friends. Furthermore, if your college is in a city like Lancaster, you get to experience a walkable downtown with a produce market, coffee shops, restaurants and bookstores. Sadly, this highly integrated and socially cohesive style of living is not available to the majority of Americans (52% of U.S. households describe their neighborhoods as suburban and 21% describe their neighborhoods as rural). Most people can’t pop out to the shop for a few minutes, or take a stroll to the nearby bakery or roadside cafe, or meet up with friends at the town square or communal gardens. When you factor in the hour-plus daily commute to and from work, most people in the U.S. today lead highly individualized lives, where social connection requires real effort to achieve.

The focus then turns to the cars we hope will narrow these rifts within our communities, but they only provide a temporary anesthetic for the problem. They treat the symptoms without addressing the root cause of why we have to drive long distances to see our friends, buy groceries, or why we have to queue up at drive-throughs and speak into a microphone just to get some Starbucks. That is why the second part of this article will focus on looking at the origins and unkept promises of suburban living, and pointing out how walkable communities with reliable public transportation and mixed-use housing can be a reality and not just a luxury reserved for college campuses or a summer vacation in Europe.

Junior Ian Rubimbura is a Contributing Writer. His email is irubimbu@fandm.edu.